Dream Houses of the Future of the Past

The lost art of sorrow.

Today on my bike I rode past a block of houses in Silver Spring that had been built in the late 1950s or early 1960s, in the once-futuristic style that characterized homes of that period. Unexpectedly, I was filled with something that felt like melancholy, a sense of loss. For what? Maybe for the families that had dreamed of owning their first home, in those years so filled with hope for some of us. Gone, now, most of them. And maybe for whatever those dreams became as the years passed.

Or maybe I felt that sense of loss, not for the families that once lived there, but for a nation that once dreamed of providing dream homes of the future for everyone. It doesn't dream that way anymore. These days, in the sunset of the American Century, survival is enough of a dream.

Or maybe the sense of loss was for me.

According to my understanding, the Arabic word for the emotion I felt is huzn, which conveys a sense of loss for what has passed and will not return. The emotion can be useful, a thread from which to weave a more constructive life. It ends upon reaching the infinite. Huzn can be beautiful, even sweet. That must be especially true than for people who are no longer young. We walk a highway paved with the bones of the past. Why not hear them sing?

In the early 1960s I was a small boy fascinated with architecture, design, and all things futuristic. I was so impressed with the San Francisco Bay Area’s plans for the BART mass transit system that I wrote to the appropriate transit authority at the age of 9 or 10 asking for more information. My mother added a stamp to my handwritten letter and dropped it at the post office. For years afterward, plan documents and annual reports would regularly arrive in the mail, replete with all the appropriate financial data. “They think you're a potential investor,” my mother said once.

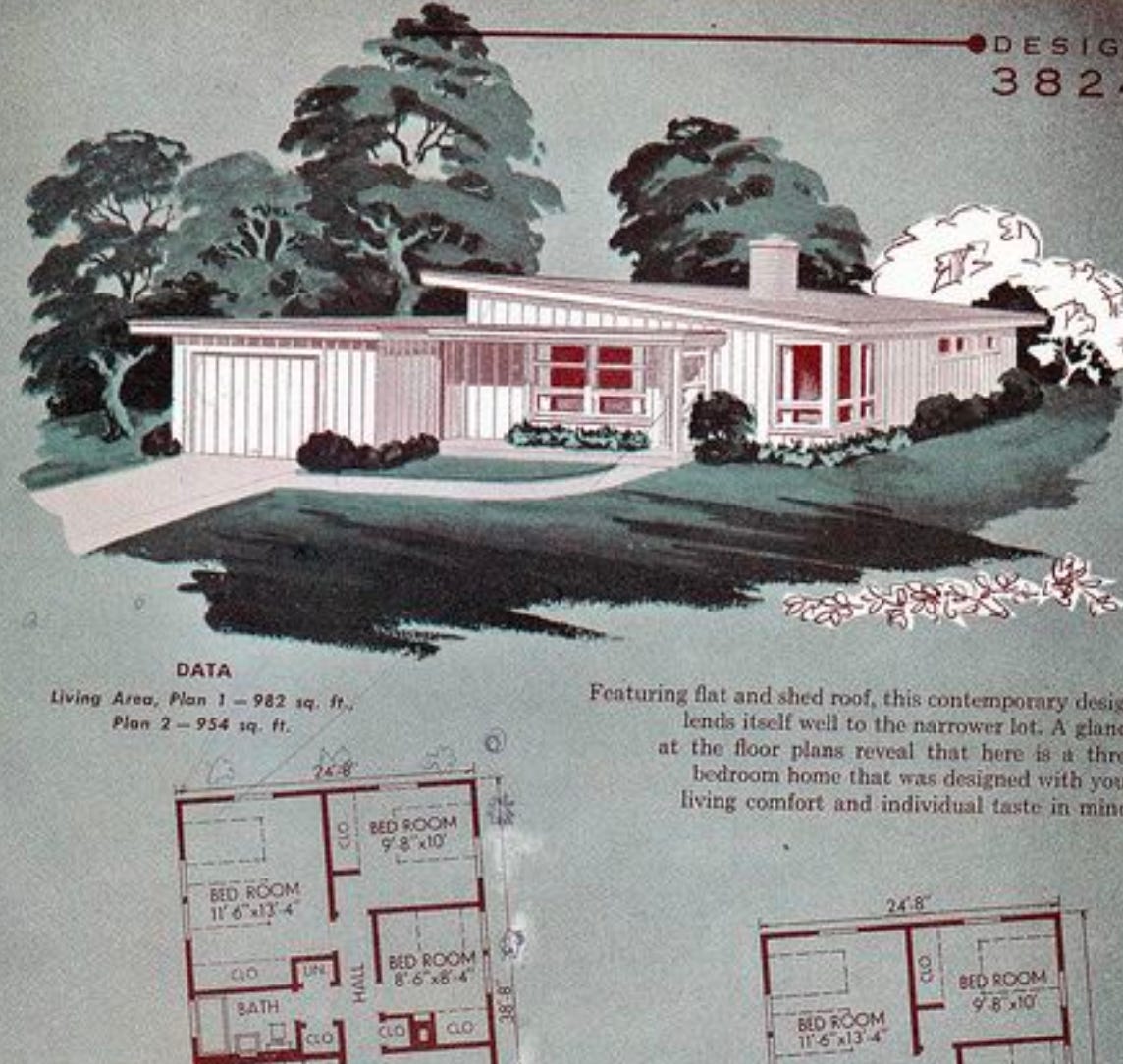

If the childhood me saw the blueprints of these houses, they would have seemed like dream homes. Like BART, or my science fiction novels, or the books of Bauhaus architecture on my shelf, they would have held the promise of a future where I was safe from the pain of my present. How could there be any suffering inside lines so symmetrical, so bold? Each stroke of the architect’s pen angled toward a parallax future where shadows and light collapsed into a dimensionless point and disappeared.

I would rather be here today with my huzn than back in the early 1960s with my science fiction books and annual reports. But then, for me at least, the parallel lines are that much closer to convergence.

I’m sure most of those houses are lovely places. Whoever lives there is better housed than 99 percent of the world’s population. And I’m sure most of these homes still hold someone’s dreams.

Many of the houses I saw on today’s ride were built from brick. I recently learned the reason there are so many brick houses around here. The great factories of Baltimore were made out of brick. As the jobs slipped away from the industrial northeast in the postwar era, the factories were torn down. Brick became plentiful and cheap, so developers bought it by the truckload. Thousands of brick homes went up across the state, each built on the dreams of the past, each cradling the dreams of a future that was never to come.