Top o' the Late Stage Capitalism to Ya

The Apocalypse After St. Patrick’s Day

March 17 is a strange holiday. For the roughly 32 million Americans who claim Irish ancestry, sentimentality toward their country of origin is understandable. I love Ireland myself – the land, the literature, the music, the people – although I’ve been unable to find any reason to claim the place as my own. If anybody without an Irish name should be drawn to St. Patrick’s Day, it’s me. After all, this was a country that didn’t tax the income of professional writers until forced into it by the European Community. That’s my kind of place.

But this country’s celebration of St. Patrick’s Day is bizarre. It’s solely about excessive drinking and yet is still only the third most alcohol-soaked day of the American calendar. (New Year’s Eve comes first, followed by Christmas.) I didn’t enjoy March 17 even when I was still drinking. The celebrations seemed forced, even desperate.

Then why? Follow the money. An estimated $6.85 billion is spent on St. Patrick’s Day in the US, which goes a long way to explaining its enforced popularity. It’s not about the real Ireland, but about a cardboard cutout land of shamrocks and leprechauns and an ever-present, truly nauseating shade of green in every shop window.

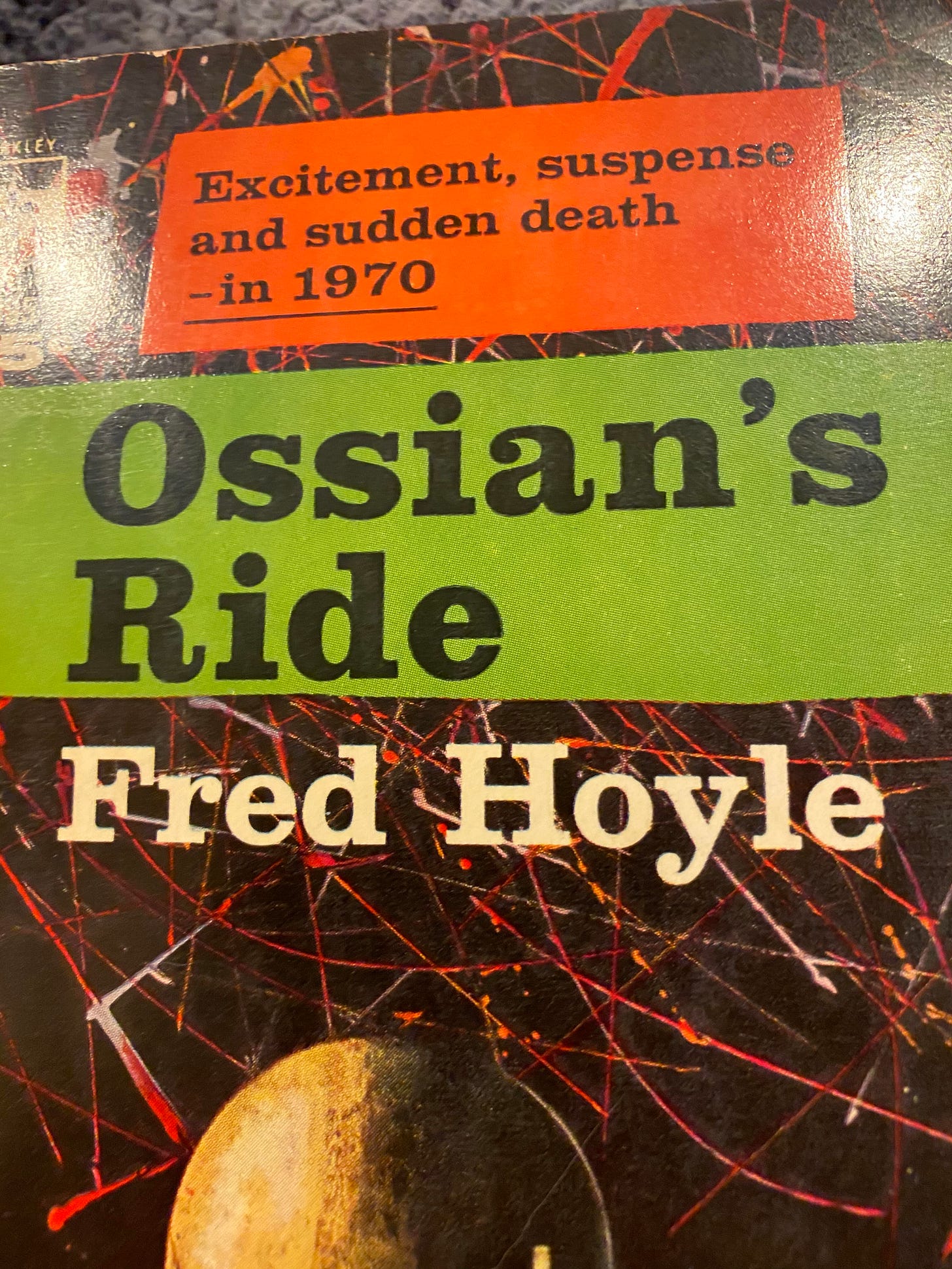

What about the real place? I first became aware of Ireland in my hometown of Utica, where our neighbors were mainly Irish and Italian Catholics. I became more aware of it when, as a young kid obsessed with science fiction, I read a novel called Ossian’s Ride by the astronomer Fred Hoyle. Written in 1959 (I probably read it in 1962 or 1963), it was set in the future year of 1970. In it the formerly backward nation of Ireland had suddenly become the world’s economic engine, thanks to the sudden invention of several world-changing new technologies on its verdant shores. (If you’re guessing the big reveal, you’re probably right.). I loved the novel, not only for its technical ideas, but for the descriptions of the green landscape and futuristic cities.

Some things are better left in memory. I recently came across my old copy (see above) and was shocked by its casual contempt for Irish culture, its colonialist and proto-fascist leanings, and its stereotyping of the people. (They learn to make a nuclear bomb out of peat, for God’s sake!) The Ireland of 1970, now called Eire, is the world’s most powerful nation – which is part of Hoyle’s joke. What he’s really saying is, how could these yokels run anything?

Hoyle’s Eire is a classic fascist state. It is governed by the leaders of a single corporation, which is the source of all those inventions, and has an all-powerful security system to record everyone’s words and deeds. The hero is a recent Cambridge graduate in mathematics – which, per Hoyle, makes him better than everyone around him. After a period of resistance, he comes to take his place in the corporate hierarchy, where he calculates he can do the most good for humanity.

Give Hoyle credit for this much: he was famously wrong about the Big Bang, but he unconsciously foreshadowed the messianic and misguided thinking of Elon Musk and his cohort.

The Ireland of 1959 still resisted the trade agreements which laid the foundation for globalism. It didn’t apply for the Common Market until 1961, two years after the book was written. In his historical memoir, We Hardly Know Ourselves, Fintan O’Toole describes 1950’s Ireland as a nation that strongly resisted outside influences, cultural and economic, a stance that drove emigration. (I assume the title refers to the song, “Johnny we hardly knew ye.”)

I haven’t finished the book and can’t render a final opinion on it. But Ireland was a sad place back then in O’Toole’s telling: beholden to the Church, culturally and sexually repressive, and overworking itself to build enthusiasm for Irish arts and sports. (The classic documentary, “The Rocky Road to Dublin,” draws the same conclusion.)

Ireland wasn’t admitted into the European Economic Community (EEC) until 1973. The country, a longtime economic laggard in the European community, briefly became a shining star of neoliberalism. The “Celtic Tiger,” they called it; a strange choice of words, since there are no tigers in Ireland. (Perhaps St. Patrick drove them out, along with the snakes? Oh, right, they never had snakes in Ireland.)

The Celtic boom collapsed when bankers shattered the world economy in 2007-2008. Apparently, he who rides the Celtic Tiger cannot dismount. While the nation has rebounded considerably since then, at what cost?

Ireland has held its own in the world economic order since 2008, but it hasn’t excelled. A study from the think tank Social Justice Ireland found that, while it has the second-highest per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the European community, it performs below par on many indicators of social well-being: seventh in income equality, for example, eleventh in gender equality, and highest in obesity. It also does poorly on water quality and climate action.

Where, then, is all that money going? As the study’s authors note, Ireland’s GDP saw a “dramatic jump in 2015,” rising more than 25 percent in one year. They add,

“This break was facilitated, at least partly, by a few multinational corporations using Ireland’s low corporate tax rate as an incentive to ‘book’ profits in Ireland for activity that takes place in other countries. Some of these companies are so large relative to the size of the Irish economy that their efforts to avoid taxation greatly distorted Ireland’s estimate of GDP.”

Even before that, corporations like Apple were taking advantage of Ireland’s artificially low taxes. As I wrote in 2013, “Even though only four percent of (Apple’s) workforce is based in Ireland, and only a small percentage of its profits are earned in that country, Apple recorded 65 percent of its worldwide profits there.” The deal Apple cut with Ireland gave it a tax rate of 2 percent, and it didn’t even pay that in some years. Talk about the luck of the Irish!

Other American companies, including Google, Facebook, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and Citigroup, also used Ireland as a tax haven. I guess St. Patrick didn’t drive all the snakes out of Ireland.

As Social Justice Ireland’s authors point out, per capita increases in the GDP do less and less for the average person’s quality of life as the overall economy grows. This is especially true when, as is true of Ireland, much of that new wealth goes untaxed or under-taxed. The authors also point out that “once again ... the Nordic countries, along with the Netherlands, top the index rankings.”

There’s a hint for Ireland’s future, and our own.

The problems that plague Ireland today are the problems that plague the world: inequality, poor nutrition, climate, and social injustice. They’re getting worse, not better. They could even be the signs of a coming collapse, drive by the depredations of what has come to be called “late-stage capitalism.” Thinking about that will make you sicker than a St. Patrick’s Day hangover.

Fred Hoyle thought he was forecasting a technology-driven utopia. Instead, he sketched the outline of a corporate-run nightmare world whose every discovery was used for private gain and private power. In that, at least, he was prescient. But we don’t need another Cambridge-educated “hero” to make things right; as the anticolonialist rebels of Ireland and the world have demonstrated, we can do it ourselves.

Enjoyed the piece. The underbelly of the monster called global capitalism and who actually benefits.